Some definitions

Anger is a feeling or emotion that ranges from mild irritation to intense feelings of fury and rage. It’s a natural response to situations:

- where we might feel threatened

- where we feel someone has unnecessarily wronged us

- we might feel harmed.

People can experience anger when someone close to them is threatened or harmed. They can also experience anger if their needs, desires and goals aren’t met.

When we become angry, we might lose our patience and act impulsively, aggressively or violently. People often confuse anger with aggression.

Aggression is behaviour that’s intended to cause harm to another person or damage property. This behaviour can include verbal abuse, threats, or violent acts.

Anger is an emotion and does not necessarily lead to aggression. Therefore, a person can become angry without acting aggressively.

A term related to anger and aggression is hostility.

Hostility refers to a complex set of attitudes and judgements that motivate aggressive behaviours. While anger is an emotion and aggression is a behaviour, hostility is an attitude that involves disliking others and evaluating them negatively.

In this article, you’ll learn helpful strategies and techniques for anger management, to express anger in alternative ways, change hostile attitudes, and prevent aggressive acts, such as verbal abuse and violence.

How do I know when anger is a problem?

Anger can be a problem when it’s felt too intensely, frequently or is expressed inappropriately. When you feel intense anger, frequently, it can place extreme physical strain on the body. During prolonged and frequent episodes of anger, certain areas of the nervous system become highly activated. It may cause an increase in blood pressure and heart rate that stays elevated for long periods, thus causing hypertension, heart disease and diminished immune system efficiency.

Another compelling reason to control anger concerns the negative consequences that result from expressing anger inappropriately. In the extreme, anger may lead to violence or physical aggression, which can result in numerous negative consequences, such as being arrested or jailed, being physically injured, being retaliated against, losing loved ones, being terminated from a substance abuse treatment or social service program, or feeling guilt, shame, or regret.

Even when anger does not lead to violence, the inappropriate expression of anger, such as verbal abuse or intimidating or threatening behaviour, often results in negative consequences. For example, it’s likely that others will develop fear, resentment, and lack of trust toward those who subject them to angry outbursts, which may cause alienation from individuals, such as family members, friends, and co-workers.

Payoffs and consequences

The inappropriate expression of anger, initially, has many apparent payoffs. One payoff is being able to manipulate and control others through aggressive and intimidating behaviours. Others may comply with someone’s demands because they fear their verbal threats or violence. Another payoff is the release of tension that occurs when one loses his or her temper and acts aggressively. The individual may feel better after an angry outburst, but everyone else may feel worse.

In the long term, however, these initial payoffs lead to negative consequences. For this reason, they’re called “apparent” payoffs because the long-term negative consequences outweigh the short-term gains.

For example: Consider a father who persuades his children to comply with his demands by using an angry tone of voice and threatening gestures. These behaviours imply to the children that they will receive physical harm if they are not obedient. The immediate payoff for the father is that the children obey his commands. The long-term consequence, however, may be that the children learn to fear or dislike him and become emotionally detached from him. As they grow older, they may avoid contact with him or refuse to see him altogether.

Related: Myths about anger

Anger as a habitual response

Anger is learned and it can become a routine and predictable response to many situations. When anger is displayed, frequently and aggressively, it can become dysfunctional and result in negative consequences. People with anger management problems tend to resort to aggressive displays of anger to solve their problems, routinely and without thinking about the negative consequences they may suffer. They may not also consider the debilitating effects it can have on those around them.

Anger management

Becoming aware of anger

To break the anger habit, you must develop an awareness of the events, circumstances, and behaviours of others that trigger your anger. This awareness also involves understanding the negative consequences that result from anger.

For example: You may be in line at the supermarket and become impatient because the lines are too long. You could become angry, then boisterously demand that the checkout clerk call for more help. As your anger escalates, you may become involved in a heated exchange with the clerk or another customer. The store manager may respond by having a security officer remove you from the store. The negative consequences that result from this event are not getting the groceries that you wanted and the embarrassment and humiliation you suffer from being removed from the store.

Strategies for controlling anger

In addition to becoming aware of anger, you need to develop strategies to effectively manage it. Anger management strategies can be used to stop the escalation of anger before you lose control and experience negative consequences. An effective set of strategies for controlling anger should include both immediate and preventive strategies.

Immediate strategies include taking time out, deep-breathing exercises, and thought stopping. Preventative strategies include developing an exercise program and changing your irrational beliefs. These strategies will be discussed in more detail.

Time out

One example of an immediate anger management strategy worth exploring at this point is time out. Time out can be used formally or informally. For now, we’ll only describe the informal use of time out. This use involves leaving a situation if you feel your anger is escalating out of control.

For example: You may be a passenger on a crowded bus and become angry because you perceive that people are deliberately bumping into you. In this situation, you can simply get off the bus and wait for a less crowded bus.

The informal use of time out may also involve stopping yourself from engaging in a discussion or argument if you feel that you are becoming too angry. In these situations, it may be helpful to call a time out or give the time out sign with your hands. This lets the other person know that you wish to immediately stop talking about the topic and are becoming frustrated, upset, or angry.

Anger meter

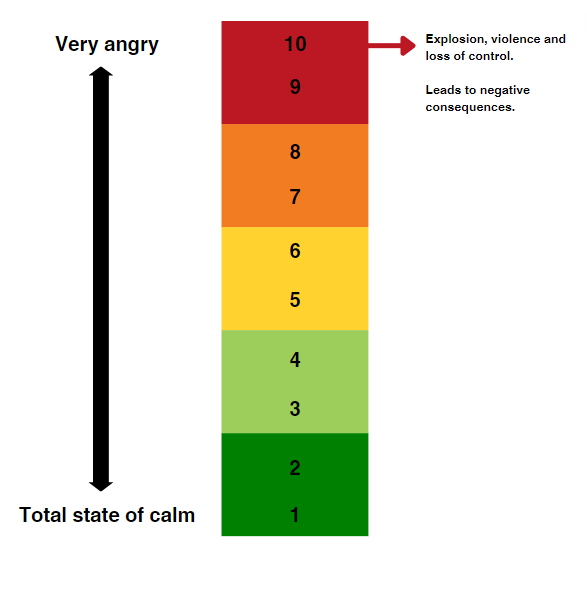

One technique that’s helpful in increasing the awareness of anger is learning to monitor it. A simple way to monitor anger is to use the anger meter. A score of 1 on the anger meter represents a complete lack of anger or a total state of calm, whereas a 10 represents a very angry and explosive loss of control that leads to negative consequences. Points between 1 and 10 represent feelings of anger between these extremes.

The anger meter monitors the escalation of anger as it moves up the scale. For example, when a person encounters an anger-provoking event, they won’t reach a 10 immediately. Although, it may sometimes feel that way. A person’s anger starts at a low number and rapidly moves up the scale. There is always time, provided one has learned effective coping skills to stop anger from escalating to a 10.

One difficulty people have when learning to use the anger meter is misunderstanding the meaning of a 10. A score of 10 is reserved for instances when an individual suffers (or could suffer) negative consequences. An example is when an individual assaults another person and is arrested by the police.

A second point to make about the anger meter is that people may interpret the numbers on the scale differently. These differences are acceptable. What may be a 5 for one person may be a 7 for someone else. It is much more important to personalize the anger meter and become comfortable and familiar with your readings of the numbers on the scale. In general, however, a 10 is reserved for instances when someone loses control and suffers (or could suffer) negative consequences.

Events that trigger anger

Certain everyday events can provoke your anger and specific events can touch sensitive areas of your life. Red flags usually refer to long-standing issues that can lead to anger. For instance, some of us may have been slow readers as children and may be sensitive about our reading ability. Although we may read well now as adults, it could still cause us to be sensitive about this issue.

In addition to events experienced in the here-and-now, you may also recall an event from your past that made you angry. You might remember, for example, how the bus always seemed to be late before you left home for an important appointment. Just thinking about how late this made you in the past can make you angry in the present. Another example may be when you recall a situation involving a family member who betrayed or hurt you in some way. Remembering this situation, or this family member, can raise your number on the anger meter.

Cues to anger

Another aspect for monitoring anger is identifying the cues that occur in response to an anger-provoking event. Cues serve as warning signs that you’ve been angry and that your anger is continuing to rise. They can be broken down into four categories: physical, behavioural, emotional and cognitive.

Physical cues

Physical cues involve the way our bodies respond when we become angry. For example, our heart rates may increase, we may feel tightness in our chests, or we may feel hot and flushed. Physical cues can warn us when anger is escalating out of control or approaching a 10 on the anger meter. We can learn to identify these cues when they occur, in response to an anger-provoking event.

Can you identify some of the physical cues that you’ve experienced when you have become angry?

Behavioural cues

Behavioural cues involve the behaviours we display when we get angry, which are observed by other people around us. For example, we may clench our fists, pace back and forth, slam a door, or raise our voices. Behavioural responses are the second cue of our anger. As with physical cues, they are warning signs that we may be approaching a 10 on the anger meter.

What are some of the behavioural cues that you have experienced when you have become angry?

Emotional cues

Emotional cues involve other feelings that may occur concurrently with our anger. For example, we may become angry when we feel abandoned, afraid, discounted, disrespected, guilty, humiliated, impatient, insecure, jealous, or rejected. These kinds of feelings are the core or primary feelings that underlie our anger. It’s easy to discount these primary feelings because they often make us feel vulnerable. An important component of anger management is to become aware of, and to recognize, the primary feelings that underlie our anger. In these articles, we’ll view anger as a secondary emotion to these more primary feelings.

Can you identify some of the primary feelings that you’ve experienced during an episode of anger?

Cognitive cues

Cognitive cues refer to the thoughts that occur in response to an anger-provoking event. When people become angry, they may interpret events differently. For example, we may interpret a friend’s comments as criticism, or we may interpret the actions of others as demeaning, humiliating or controlling. Some people refer to these thoughts as ‘self-talk,’ because they resemble a conversation, we’re having with ourselves.

For people experiencing anger issues, this self-talk is usually very critical and hostile in tone and content. It can reflect beliefs about the way we think the world should be beliefs about people, places and things.

Closely related to thoughts and self-talk are fantasies and images. We view fantasies and images as other types of cognitive cues that can indicate an escalation of anger. For example, we might fantasize about seeking revenge on a perceived enemy or imagine or visualize our spouse having an affair. When we have these fantasies and images, our anger can escalate even more rapidly.

Can you think of other examples of cognitive or thought cues?

Cues to anger: The four cue categories

- Physical: Increased heart rate, tightness in chest, rapid breathing, tenseness in muscles, feeling hot or flushed.

- Behavioural: Pacing, clenching fists, grinding teeth, raising voice, glaring.

- Emotional: Fear, hurt, jealousy, guilt, impatience.

- Cognitive/Thoughts: Hostile self-talk, images of violence or aggression, imagining revenge, remembering past hurts.

Still need help?

Anglicare Southern Queensland provide a range of counselling and support services for men who are wanting to create safety, respect and partnership in their current or future relationships. To learn more about our Living Without Violence program or other counselling services, please visit: